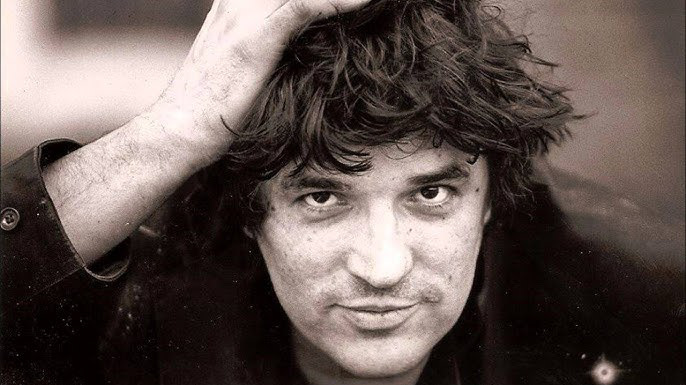

It Takes Two: Robbie Robertson and Richard Manuel's Underrated Songwriting Partnership

Popular music is littered with popular songwriting pairs. The combination of two songsmiths has gifted the world with hundreds of hit songs. Some of the most successful in pop are The Beatles, Paul McCartney and John Lennon, The Rolling Stones, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger and Elton John with Bernie Taupin. The ability to have an equal partner tends to be one of the most successful combinations to unlock the best songs. The ability to trade back ideas, focus on specific areas like lyrics or melody and bring them together to craft the perfect piece has been seen through the listed examples above and countless others.

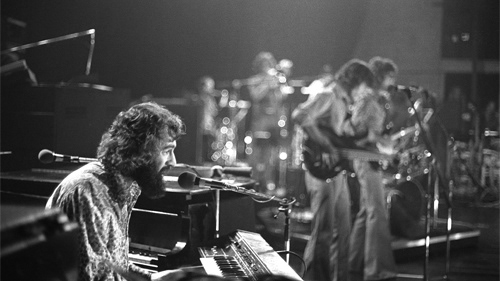

When it comes to The Band, there was indeed a songwriting relationship between Richard Manuel and Robbie Robertson. Bizarrely, that relationship is not highlighted. Given they created some of the best songs of the 1960s together, I wanted to dive into the topic deeper to understand why that might be so and explore the songs themselves via the partnership that should put Robertson and Manuel up there with the best.

First, it could be debated whether the lack of volume is reason enough not to earn the praise of their peers. There are only seven songs officially credited to the duo in The Band’s catalogue, and those are “Katie’s Been Gone,”, "Ruben Remus", “Jawbone,” “Whispering Pines,” “When You Awake”, “Sleeping,” and “Just Another Whistle Stop.”

Quality over quantity is easily argued in the case of Robertson and Manuel. When you look at the list none of the aforementioned songs are what you’d consider their biggest hits, but to a fan of The Band, it’s pretty clear some of the songs are amongst the most beloved. The Band was never about quantity. They weren’t pumping out a plethora of material every six months and are only heralded for three to four of their albums.

Second, I cautiously probe the songwriting credit debate as a potential reason why the pairing never received acclaim. Given that Helm and Danko have on occasion mentioned the lack of due songwriting credits on songs (The Band’s song “Twilight”, Danko argues is a Danko and Robertson co-write) you begin to wonder if more songs in The Band’s catalogue could have easily been credited to Robertson and Manuel. It’s claimed that twenty percent of “The Weight” lyrics were composed by Manuel, or in music professor, Neil Minturn’s works he explains that Manuel had created a substantial part of the music in The Band’s classic “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” Without the formal credit, it becomes harder to put the Robertson/Manuel partnership up on a pedestal.

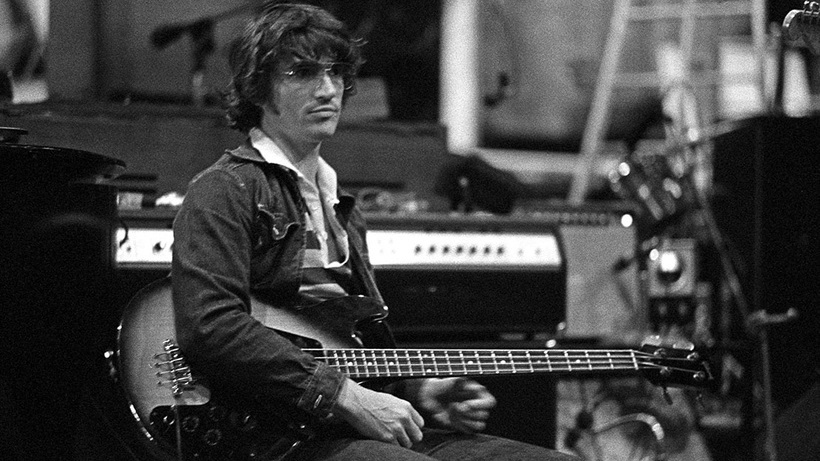

Third, is The Band’s overall narrative. Again, talked about endlessly, Robertson controlled much of the mythmaking around The Band from the very beginning. With the press-shy Manuel never giving much in formal interviews on his songwriting, his passing in 1986 did him no favours in supporting his songwriting legacy. There is a weird dual narrative around the group. On one hand, Robertson focuses on the groups' collaborative skills, their brotherhood and how their contribution was critical to their critical success. On the other hand, Robertson tends to focus on the songs he is credited as a solo writer, he scantly mentions his co-written songs, the process or the collaboration that unfolded.

While it is fair to say he asked about “The Weight” rather than “Sleeping,” It’s strange that Robertson doesn’t offer up more on “Whispering Pines” or “Just Another Whistle Stop,” given they are relativity popular in The Band community. He does talk about The Band’s collaborative nature in every other aspect. This has undoubtedly altered the respect for Manuel and Robertson’s collective efforts. Would it be too bold to say Roberton tries to minimize these collaborations in the songwriting department?

With that context provided, I want to pivot to the songs themselves. I want to argue against the prevailing narrative and provide praise for their collaborative effort. As mentioned previously, seven songs were the bulk of their official co-written credits on their studio efforts and I will be focusing on four in particular.

Let’s start with the earliest known co-written song 1967’s “Katie’s Been Gone.” The song was created sometime during The Basement Tapes period, leading to the recording of their first studio effort Music From Big Pink in 1967. American Songwriter critic Davis Inman summarizes the early partnership of Robertson and Manuel so well, “Katie’s Been Gone is a marriage of Manuel’s longing lyrical sense and Robertson’s tight songcraft.”

Supposedly written as an ode to singer Karen Dalton, the lyrics are from the perspective of an abandoned lover, as Katie the namesake of the song has fleed. Lyrically, this is an early example of Manuel’s focus on love, loss, sadness and isolation. Most likely mirroring his depression and anxieties. For example,

“Dear Katie, if I'm the only one,

How much longer will you be gone?

Oh, Katie, won't ya tell me straight:

How much longer do I have to wait?”

How much longer will you be gone?

Oh, Katie, won't ya tell me straight:

How much longer do I have to wait?”

The song doesn’t follow a strong chorus/verse structure but every stanza of lyrics starts with mentioning Katie directly. Without a typical chorus, Robertson creates an incredibly straightforward, economic chord structure that allows Rick Danko to inject his loop rhythm with Levon Helm and Garth Hudson's breathy keys. As writer Barney Hoskyn later noted, “Katie’s Been Gone” was “the birth of the Band.” He is certainly correct. The song is a definitive mark in The Band’s changing style and approach to songcraft. The poetic romanticism of the lyrics and abstemious song structure mark a valiant first effort in the Robertson and Manuel songwriting partnership.

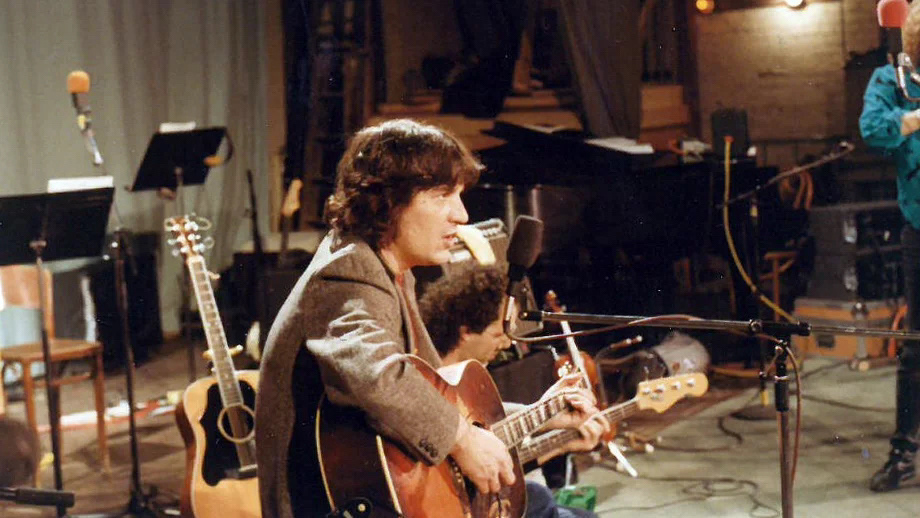

“Whispering Pines” is perhaps the strongest of the Manuel and Robertson partnership. A ballad, one of the last songs recorded when The Band travelled to Los Angeles to record the album. Richard had written the music and melody behind a piano in his Woodstock home that painter George Bellows had left behind. Manuel later mused on writing, “I lean more into chord changes and melodic stuff. I can write music very easily, but when it comes to words… it's hard to get those words in the right slot…”

Together with Robertson, they pieced together the song with lyrics. According to Robertson, "Richard always had this very plaintive attitude in his voice, and sometimes just in his sensitivity as a person. I tried to follow that, to go with it and find it musically. We both felt very good about this song." Robertson illustrates the beautiful nature of their partnership, whether each person brings lyrics or music they knew how to write for each other and the wider group. Robertson had an uncanny ability to write lyrics to fit the singer, whether Manuel, Danko or Helm.

Critically, “Whispering Pines” was lauded as a triumph. Bill Janovitz for Billboard Magazine called it, “one of The Band’s most beautiful songs, if not the most gorgeous” and author Goerge Case wrote that “Whispering Pines” is “one of the most haunting ballads in rock n’ roll”. Overall, “Whispering Pines” is the ultimate example of the success of the Manuel and Robertson songwriting partnership. The combination of sorrowful melody and potent, image-filled lyrics provided The Band and audience with one of their finest tracks.

“Jawbone” is one of those songs mostly overlooked on an album filled with songs like “Up On Cripple Creek” and “Whispering Pines” but any serious fan of The Band’s second studio album often finds that “Jawbone” offers up something that very few other do. Richard Manuel as a writer often pushed the most boundaries in terms of The Band’s sonic landscape early on. Whether that be the psychedelics of “In A Station” on their first album, we are back with his next venture via the progression of “Jawbone”.

What makes this song so unique is Manuel’s penance for experimentation, by no means is this a prog-rock song, but it has sensibilities of such while mixing in the down-to-earth, blue-collar, shambolic nature of other songs on the album. Levon Helm later jokingly said, “Richard wasn’t happy until he made me change rhythm patterns at least twice…” with Manuel’s pushing The Band found new ground.

Paired with a complex musical sequence are Robertson’s lyrics. Following the themes that helped make The Band popular, the story follows a down-and-out character, someone who steals, gambles, and cheats but is also a hard-working man, barely keeping his own. Robertson’s words are simple but that doesn’t stop him from painting a refined portrait with lines line:

“Boostin' and goin' out on the lam

Ya know that you'll steal anything that you can

Temptation stands just behind that door

So what you wanna go and open it for?”

Ya know that you'll steal anything that you can

Temptation stands just behind that door

So what you wanna go and open it for?”

Moreover, Robertson always gives even the most deceitful characters something redeemable. With his yet again simple three-line chorus, he lets you in as the listener to the exploits of the character with, “I'm a thief, and I dig it! / I'm up on a reef, / I'm gonna rig it! /I'm a thief, and I dig it!”. It’s simple and effective and how can you not sing along?

Overall, the complex musical attributes counterbalanced by the unadorned lyrics show Robertson and Manuel again at their best. They balance each other's skillset and deliver a wonderfully original song.

“For the life we chose, in the evening we rose / Just long enough to be lovers again / And for nothing more / The world was too sore to live in” is the heartbreaking and emotive opening to one of Robertson and Manuel’s last co-written contributions with “Sleeping” which was also the b-side to their third studio album Stage Fright in 1970. The song is what Barney Hoskyn’s called “one of Richard [Manuel's] liveliest performances" and "one of The Band's most intricate arrangements."

“Sleeping” combines many of the brilliant characteristics of previous Robertson and Manuel contributions. A spiritual successor to “Whispering Pines” with its unabashed emotion but it also is similar to Richard Manuel’s “In A Station” with its relaxed and airy feel and Robbie Robertson’s “King Harvest” with no traditional chorus instead, the verses that are sung softly are given greater importance. Furthermore, Manuel and Robertson dramatize how sleeping provides man with a crucial escape from the haste of life– a motif that can be delineated back in the partner's “When You Awake”.

Another exciting component of this song is that Robertson and Manuel pose so many of the lyrics are questions. They don’t provide the audience with answers. Passages like:

“The hoot owl and his song will bring you along

Where else on earth would you wanna go?

We can leave all this hate before it's too late

Why would we wanna come back at all?”

Where else on earth would you wanna go?

We can leave all this hate before it's too late

Why would we wanna come back at all?”

Manuel spends a lot of his time searching in his lyrics and finding the answers. The tandem pair these lyrics with the musical arrangement in such a fascinating way. The use of a waltz time signature is interesting, the song starts focused confidently on Manuel and his vocal and piano before expanding to the entire band. However, the rhythm of Danko and Helm rush and drag at points in the song to give the feel of a typical verse/chorus structure without being confined by it. This seems more characteristic of Manuel’s typical prose than Robertson’s.

Robertson places a solo in the song's middle that is a counter to the sensitive lyrics. It’s searing and emotive in a different way, which beautifully interplays with Garth Hudson’s pitch-bending Lowrey organ. Most songwriters wouldn’t be confident in placing the lyrics they wrote with the music the way Robertson and Manuel are. In many ways what is laid out is a series of juxtapositions, together it works. It’s magical, and the pair's alchemy makes “Sleeping” a rather excellent song.

As I outlined earlier, there are many reasons why the tandem of Robertson and Manuel isn’t highlighted as much as I believe they should. I am also not naive; The Band is a footnote for many, a group that doesn’t have a consistent output and doesn’t hold a cultural footprint like The Rolling Stones or The Beatles. What can I say, I am a fanboy, a “Band cultist.” But in the spirit of trying to remain as objective as possible, I believe Robertson and Manuel were able to craft some of the most uniquely original songs that balanced various genres and influences while also providing catchy and lasting work. It would not be an overreach to say the pair's efforts led to the impact of generations of musicians that followed them.

For more content consider contributing to The Band: A History's Patreon and listening to our Deep Cuts Playlist on Spotify.